80% Reduction in patent fees for Educational Institutions – A much awaited booster for patenting new Ideas in India

Indian Educational Institutions have been the hub of some of the most innovative minds. An amalgamation of ideas from a student and teacher during a learning process can foster substantial innovation. But one thing that was lacking so far was the affordability to legally own and monetize these ideas by the fraternity in educational institutions.

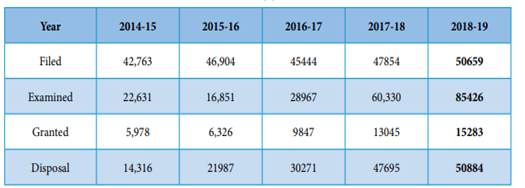

The Annual report of the Indian Patent office for the year 2018-19 indicated that the number of patents filed have steadily increased on a yearly basis as shown below:

Trends in Patent Applications:

Courtesy: Annual Report 2018-19 by Indian Patent Office

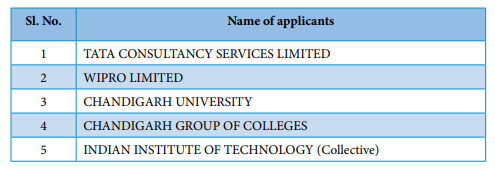

However, when we look at the top 5 Indian applicants for patents, we observe that very few educational institutions make it to the top 5 applicants’ list in India. Also, the number of patents filed by all the educational institutions in India put together is hardly 2% of the total number of patents filed in India.

Top 5 India applicants for patents in the field of Informatioon Technology

Courtesy: Annual Report 2018-19 by Indian Patent Office

Therefore, a rebate of 80% according to the notification published on 21st September 2021, by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, will now attract more and more projects to be filed and monetized by educational institutions across the nation. In accordance with the notification, the Central Government has made certain rules to amend the Patent Rules, 2003. The amended rules are called Patent (Amendment) Rules, 2021, and has come into force on the date of their publication in the Official Gazette. The key takeaways of the notification are as follows:

|

Sl. No |

Rules |

Sub-Rule |

Inference |

|

1. |

2 |

(ca) “educational institution” means a university established or incorporated by or under Central Act, a Provincial Act, or a State Act, and includes any other educational institution as recognized by an authority designated by the Central Government or the State Government or the Union territories in this regard; |

All the universities and other educational institutions recognized by any one of the Central Government, State Government or Union Territories will hence forth be recognized as “educational institution” by the Indian Patent Office for categorizing under the right fee slab. |

|

2. |

7 |

(1) Provided further that in the case of a small entity, or startup, or educational institution, every document for which a fee has been specified shall be accompanied by Form-28. |

The filing fee for educational institution is same as the filing fee for a natural person, small entity or a startup. |

|

|

|

(3) In case an application processed by a natural person, startup, small entity or educational institution is fully or partly transferred to a person other than a natural person, startup, small entity or educational institution, the difference, if any, in the scale of fees between the fees charged from the natural person, startup, small entity or educational institution and the fees chargeable from the person other than a natural person, startup, small entity or educational institution, shall be paid by the new applicant along with the request for transfer. |

In case the educational institution chooses to transfer their processed application to any entity other than a natural person, small entity or a startup, the difference in the chargeable fees must be paid by the new applicant. |

|

3. |

First Schedule |

Headings and sub-headings in Table 1. |

“educational institution” is included in the heading and sub-heading of Table 1 along with natural person, small entity and a startup. |

|

4. |

Second Schedule |

Form 28 |

“educational institution” is included in Form 28 along with natural person, small entity and a startup. |

Who will qualify as an educational institution?

In accordance with the newly amended Rule (2) (ca), for an Indian applicant, an “educational institution” is a university established or incorporated by or under Central Act, a Provincial Act, or a State Act. Further, any other educational institution recognised by an authority designated by the Central Government or the State Government or the Union territories will also be recognised as an educational institution in India. A foreign applicant can qualify as an educational institution by furnishing any legal document to ascertain the same.

How can an educational institution claim the benefits of educational institutions?

In accordance with the newly amended Rule (7), the educational institutions are recognized on par with a small entity or a startup and are therefore entitled to file the required documents using the new Form -28. Further, the scale of fees chargeable for an educational institution is on par with a small entity or a start-up.

CONCLUSION

Most of the educational institutions take a minimum of 10 years to establish themselves. Their profits do not alter according to the industrial requirements. Therefore, recognizing them on par with a small entity thereby reducing the filing fees by 80%, will make it easy for young innovators to legally protect their innovations.

Further, the provision of 80% rebate for filing patents by educational institutions seems like a win – win opportunity for both the government as well as the educational institutions. On one hand, by reducing the filing cost for patents filed by educational institutions, the Government has channelized the innovative ideas towards strengthening the Indian Economy. On the other hand, a greater number of educational institutions will now be willing to file patents of innovative projects carried out by students under the guidance of their respective mentors. This in turn will provide an added income to the educational institutions once the patents are monetized.

Moving in this direction, the Andhra University has welcomed the new rule by setting up an exclusive centre for Intellectual Property (IP) within its campus. The IP centre will henceforth oversee the documentation process and bear the cost of filing for IP rights of researchers in Andhra University. On the whole, this new rule has set a platform to utilize the vibrant young minds towards building a strong economy thereby contributing to the growth of the nation.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Compulsory Licensing in view of Pandemic: Bajaj Healthcare requests for license to manufacture Baricitinib

Baricitinib is a drug for treating rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in adults whose disease was not well controlled by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors. It acts as an inhibitor of Janus kinase (JAK), blocking the subtypes JAK1 and JAK2.

However, in the recent times, during the pandemic, Baricitinib has been used in combination with Remdesivir to effectively treat Covid patients. Baricitinib inhibits the intracellular signaling pathway of cytokines such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, interferon-γ, and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor, thereby improving the lymphocyte count and preventing entry of the coronavirus into the cell.

Eli Lily and Company, originally based in the United States, is the authorized licensee for Baricitinib. In the backdrop of the second wave of COVID in India, NATCO Pharma approached the Controller of Patents on 3rd May 2021, to request for a Compulsory License (CL) for manufacturing Baricitinib. This way they could make the drug easily accessible for a greater population of the country during the pandemic. NATCO cited a circumstance of national emergency among others under Section 92 of the Patents Act, 1970 to obtain CL for the drug Baricitinib from the Central Govt. of India.

However, the Licensee, Eli Lily inked a royalty-free, non -exclusive voluntary licensing pact with NATCO and five other Indian drug manufacturers, for manufacturing and commercialization of Baricitinib. With this, NATCO Pharma withdrew its appeal for CL for Baricitinib on May 17, 2021.

Bajaj Healthcare (BHL) failed to get the voluntary license from Eli Lily despite their repeated attempts. Therefore, BH has moved the Indian Patent Office to grant compulsory license for manufacturing & supply of the Covid drug Baricitinib (both Active pharmaceutical Ingredients and formulation) on 26th May 2021. BHL stated that the price of Baricitinib sold by Eli Lilly in India is not affordable to the public and that it can manufacture the same drug at an estimated price of Rs 14 (for 1mg), Rs 18 (2 mg), and Rs 28 (4 mg) tablet as opposed to Eli Lilly’s drug, the entire course of which, costs about Rs 45,220 per patient.

A voluntary license requires the licensee to provide permission for commercialization of the stated drug whereas, the CL does not require the permission of the licensee for the same. This way the covid drug can be manufactured and distributed at a faster pace and may help in controlling the soon anticipated third wave of Covid in India.

So far, India has issued compulsory license just once since Independence. The legal basis for providing compulsory license in the Indian Patents Act is in line with the international agreements. NATCO Pharma was granted a compulsory license in 2012 for generic production of Bayer Corp’s Nexavar, a life-saving medicine used for treating liver and kidney cancer. The CL was granted based on a test laid down under section 84(1) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970 (amended in 2005). Accordingly, the sole ground for granting the compulsory license was to make the life – saving drug more affordable for people residing in the country.

However, granting a compulsory license, under section 92 of Indian patents Act,1970, on the grounds of national emergency, to manufacture a drug for which a voluntary license has already been granted to other manufacturers in the same country, may not set the right precedence to other product manufacturers in similar scenarios. A scenario where the patent owners have already provided voluntary license to a few manufacturers within the country, may not suffice as a national emergency in the true sense. Granting a compulsory license to one manufacturer while others are already working with a voluntary license might just provide a market share for the manufacturer with the compulsory license, but not benefit the country’s population in any manner.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

South Africa grants a patent with an Artificial Intelligence (AI) system as the inventor – World’s first!!

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has gained quite a lot of momentum in the recent decade and is growing exponentially ever since. AI with all the developments and iterations is being honed to be more sophisticated and intuitive. To this day AI has been developed to a level, wherein AI is capable of carrying out certain tasks without human intervention. DABUS is one such AI system created by Stephen Thaler, that he believes was the sole inventor of two new discoveries – a fractal container and a neural flame. Stephen Thaler, the CEO of Imagination Engines, Inc., is a pioneer in the field of AI and programming. Stephen Thaler filed patent applications in 17 jurisdictions that include US, Europe, Australia, and South Africa, based on what Stephen believes, the invention was created solely by DABUS itself, and thereby naming only DABUS as an inventor. However, Stephen lists himself as an Assignee to the said patent applications and would hold the rights to the patent applications if the patent application meets the requirements by the respective Patent Office.

With all the developments in the field of AI, debates on AI being included as an inventor has been a hot topic for the intellectuals. Debates have been equally weighed with inventors wanting AI to be recognized as an inventor and few IP experts resisting the same. Amidst this discussion, the South African Patent Office broke the ice by granting patent to an application filed by Stephen with DABUS listed as a single inventor, which came as a surprise to the global community.

However, there is a catch. South Africa is a non-examining country, implying that the patent applications filed in the country are not examined to check if the requirements of patentability are met as is the case in US or India. Furthermore, the South African Patent Office does not mandate the inventor to disclose any prior art. In light of this, any patent application filed in South Africa results in getting a grant as long as all the formal requirements are met. In any case, the granted patent can be opposed by a third party and can be invalidated by proving so. Until then, the patent application stands valid in the jurisdiction. With South Africa granting patent to the patent application with DABUS listed as an inventor, many IP experts have criticized the decision and called it an oversight by the Patent Office.

Two days after the South African patent grant, on July 30, 2021 Justice Jonathan Beach of the Federal Court of Australia, in “Stephen Thaler and Commissioner of Patents” ruled in favor of Stephen’s team allowing AI to be listed as an inventor and said that “an inventor as recognized under the Act can be an artificial intelligence system or device. But such a non-human inventor can neither be an applicant for a patent nor a grantee of a patent.”. This comes after scrutinizing the Australian Patents Act 1990 and failing to find definition for “inventor”. The ruling is a big step forward for Stephen and his team.

On the other side of the spectrum, the UK Patent Office, the European Patent Office and the USPTO have rejected the patent application in the formal examination phase. The England and Wales High Court concurring with the UKIPO rejected the patent applications by Stephen’s team. The Court held that AI is not a natural person and therefore cannot be interpreted as an inventor under the UK Patents Act 1977. The European Patent Office also has rejected the patent application on the grounds that the AI systems or machines at present have no rights because they have no legal personality as compared to a natural or legal person and cannot have any legal title over their output.

The USPTO issued a notice to file missing parts for each of the applications requiring Stephen to identify an inventor by his or her legal name. In light of this, Stephen filed several petitions requesting reconsideration of the notice. The USPTO denied the application on similar grounds cited by the UK and European Patent Offices. The USPTO having considered case laws (University of Utah v. Max-Planck-Gesellschaft and Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc. and Beech Aircraft Corp. v. EDO Corp.) concerning inventorship and the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) stated that the patent application does not comply with the 35 U.S.C § 115(a), as DABUS (or invention generated by AI) is being listed as an inventor and the current statutes, case laws and USPTO regulations and rules limit inventorship to natural persons. In response to this, Stephen and his team filed a suit against the Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the USPTO as well as the USPTO in the Virginia federal court.

On September 02, 2021, the U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema in Alexandria sided with the USPTO on the matter stating that the USPTO pointed to the fact that, contrary to plaintiffs assertion that the "statutes relied upon by Defendants were passed long before AI-[g]enerated [i]nventions were a reality" and that if Congress had contemplated this artificial intelligence issue, it would have included artificial intelligence machines within the definition of "inventors"; Congress defined an "inventor" as an "individual" through the America Invents Act in 2011, when artificial intelligence was already in existence. See Pub. L. 112-29, § 3(a), 125 Stat. 285 (Sept. 16, 2011); see also H.R. Rep. No. 112-98 (June 1, 2011), available at 2011 U.S.C.C.A.N. 67, 67. Accordingly, plaintiffs policy arguments do not override the overwhelming evidence that Congress intended to limit the definition of "inventor" to natural persons. Brinkema also added that As technology evolves, there may come a time when artificial intelligence reaches a level of sophistication such that it might satisfy accepted meanings of inventorship. But that time has not yet arrived, and, if it does it will be up to Congress to decide how, if at all, it wants to expand the scope of patent law.

The U.S. District Judge thereby ruled that the federal law requires that an “individual” take an oath that he or she is the inventor on a patent application, and both the dictionary and legal definition of an individual is a natural person.

In light of the foregoing, how structured is the Indian Patent Law in this matter is a matter under consideration. The Indian Patent Act, 1970 does not have a specific definition for the term “inventor”. In India, an application for patent can be made by a “person” who is True and first inventor. Here the term “person” also includes the Government as per the Indian Patent Act, 1970. However, the Indian Patent Act, 1970 does provide sufficient light on the term “Assignee”.

In addition, there are very few case laws in India that correspond to “inventorship” of a patent to rely upon.

Also, assuming a case where AI is allowed to be listed as an inventor, more of hurdles would have to be addressed like:

- Transfer of patent rights

- Obtaining patent rights

- Patent oppositions

- Inclusion of AI as a party in a contract

The above-mentioned rights, under the current Indian Act are granted to a “person” and AI would be unable to perform such tasks. Therefore, with the current policy it is unlikely that an AI system would be allowed to name as an inventor or a co-inventor. Furthermore, in cases of transgression, accountability also has to be considered. For an AI system to be recognized as an inventor, the Patent Act, 1970 and the Patent Rules, 2017 have to be respectively amended and the term “inventor” has to be explicitly defined with AI system included in the definition. Also, AI system in current time is not as sophisticated and intuitive to be considered as a sole inventor. AI still requires a lot of development. Until then, inclusion of AI as inventor in India would only have ambiguity.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Post – Dating of a Patent Application – Indian Perspective

Section 17 and 9(4) of the Indian Patent Act deals with post-dating of a patent application. It shall be noted that only a complete application can be post-dated to a later date. To interpret the provisions of post -dating an application, one has to rely on the Judgement passed by Delhi High Court on MAY 26, 1999 in Standipack Private Limited & … vs M/S. Oswal Trading Co. Ltd.

The Judgement recites:

“8. The aforesaid provisions make it crystal clear that post-dating of the patent can be done only to the date of filing of the complete specifications. In the present case the Controller of Patents had filed the original records relating to the grant of patent in favour of the plaintiff. The said records reveal that the application for the grant of patent was originally filed by plaintiff on 11.4.1989 and the complete specification was filed on 11.10.1990. The Controller of Patents however, post-dated the patent to 11.7.1989 although complete specifications followed by the provisional specification was filed on 11.10.1990. Thus the post-dating of the patent by the Controller to 11.7.1989 prima facie appears to be in violation of the provisions of Section 9 of the Act. The date of the patent, therefore, should have been 11.10.1990. The patent documents referred the validity of the patent for 14 years from 11.7.1990. Thus the validity of the patent has also been ignored by the Controller of Patents. The plaintiff also during the course of arguments admitted that complete specifications were submitted on 11.10.1990, which is the date from which the Patent granted would be effective. Thus post-dating the Patent to 11.7.1989 appears to be illegal in view of the provisions of Section 9(4) of the Patent Act and the provisions of Section 17 are subject to Section 9.”

Further, section 9 (4) of the Indian patent act clearly mentions the type of application that can be post-dated which are as follows:

- A complete application filed within twelve months in pursuance of a provisional specification filed under section 9(1) and

- A complete specification filed in pursuance of section 9(3). Section 9(3) recites that a complete specification that has been filed can be converted to a provisional specification within twelve months from the date of such filing on requesting the Controller to treat the complete specification as provisional specification, provided the complete specification not being a convention application or a PCT application. In other words, the complete specification must be an ordinary application for the provision of section 9 (3).

How long an application for patent be post-dated?

An application for a patent can be post -dated only to six months from the date of filing of the complete specification. No application can be post- dated to a date later than six months from the date of such filing (Section 17).

Section 17 should not lead to violation of the provisions section 9

Section 17 can be implemented only when the provisions of section 9 are met. This implies that post-dating does not shift the filing date of the complete specification more than 12 months as required under section 9 (1). The complete specification accompanied by the provisional specification has to be filed with the twelve months from the date of filing of the provisional specification.

In this context, a brief summary and decision of the Controller w.r.t 1064/DEL/2010 is discussed herewith for better clarity.

Fact of the case:

|

Application type |

Filing date |

Controller Decision |

|

Provisional application |

06 May, 2010, |

Refused Date: 31/03/2016 |

|

Complete application |

08 August, 2011 |

|

|

Request to post date of the provisional application from 06/05/2010 to 06/08/2010 |

05 May, 2011. |

In the present case, the Applicant had filed a request to post -date the provisional application on 05, May 2011 and subsequently filed the complete specification within twelve months from the new priority date i.e., 06/08/2010. Thus, extending the prescribed time limit of filing of complete specification to 08/08/2011 lead to violation of the provisions of section 9 of the Act.

Decision of the Controller recites,

“In view of above, complete specifications followed by the provisional specification was filed on 08/08/2011, while according to section 9(1), a complete specification shall be filed within twelve month from the date of application, which is 06/05/2010. There is GAP, which could not be filled by filing request for postdating of provisional application, which could be filed anytime before the grant of Page 3 of 3 patent, leading to abandonment of application under section 9(1) of The Patents Act, 1970, and revival of application by postdating of provisional application is against Law of Nature, as once anything treated as deemed to be abandoned, cannot be reconstituted/revived. There is GAP, but, present invention could motivate more innovation and could give momentum to WHEEL OF INVENTION, having potential of industrial applicability, if any. Thus, complete specification has not been filed within the prescribed time period according to section 9(1)of The Patents Act, 1970, and accordingly the application is hereby treated as deemed to have been abandoned according to section 9(1)of The Patents Act 1970.”

Fees and Form

An applicant can file a request to post-date the complete specification by filing Form 30 and paying the prescribed fee. The request to post-date an application can be filed any time before the grant of the patent application.

Fee for filing a request to post -date a patent application:

|

Application |

Form |

For e-filing |

Physical Filing |

||

|

Natural person, start up, small entity or eligible educational institution |

Others, alone or with natural person, start up, small entity or eligible educational institution |

Natural person, start up, small entity or eligible educational institution |

Others, alone or with natural person, start up, small entity or eligible educational institution |

||

|

Post – dating an application |

Form 30 |

|

|

|

|

Examination of post – dated application:

|

Post-dating request made before examination |

Post-dating request made after examination |

|

The examination of the post-dated application is conducted considering the post- dated date as the priority date of the application. |

A fresh examination considering the post-dated date is carried, when a request to post-date, an application is made after the issuance of First Examination Report. |

Timeline to file a post- dated convention application in India

Section 136 (3) of the Indian Patent Act states that a convention application cannot be post-dated under Section 17 (1) to a later date. This implies that the convention application should be filed within twelve months from the date of the first application.

CONCLUSION:

Shifting the priority date to a new date bear the risk of including more number of prior art references with respect to the claimed invention. Additionally, one has to take utmost care to avoid violation of section 9, while applying for post-dating of a patent application as it may lead to refusal of the patent application. Therefore, one has to analyse the repercussions of the post dating a patent application before opting for such provision.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Bolar exemption: Delhi high court upholds the exploitation of patented invention for research and development purposes

Once a patent is granted the patentee has complete rights over that particular invention in the jurisdiction the patent was granted. This grant restricts everyone else from manufacturing, selling or importing said invention for a specific term, typically 20 years from the date of filing. However, Section 107A of the Indian Patents Act, also known as “Bolar provision”, offers protection against patent infringement if the patented invention is exploited by the third-party for research and development. Particularly, in case of pharmaceutical patents, the third party entities require a considerable period for getting regulatory approval for commercializing the expired patent. This results in increased term of monopoly over the patent. The provision under Section 107A also prevents this extension in the term of patent, wherein the third-party entity can perform the patented invention for research and development activities for getting regulatory approvals.

The Section 107A of The Patents Act 1970, states that,

“Certain acts not to be considered as infringement. -For the purposes of this Act,

(a) any act of making, constructing, 197 [using, selling or importing] a patented invention solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information required under any law for the time being in force, in India, or in a country other than India, that regulates the manufacture, construction, 198 [use, sale or import] of any product;

(b) importation of patented products by any person from a person 199 [who is duly authorized under the law to produce and sell or distribute the product], shall not be considered as an infringement of patent rights.”

Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. & Anr (hereafter called as ‘the plaintiff’) alleged that SMS Pharmaceuticals Limited (hereafter called as ‘the defendant’) had been exporting their patented invention, Sitagliptin, an anti-diabetic drug. The investigator working for the plaintiff learnt that the defendant had and is willing to provide Sitagliptin an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) for sale in the domestic market. Considering this along with other arguments presented by the plaintiff, on 21st October 2020, the court granted an ex-parte ad-interim injunction against the defendant in terms of prayer. Consequent to issuance of summons, the defendant responded with a written statement. The written statement asserted the fact that the defendant is a Research and Development based API manufacturing group and participates in research to obtain pharmaceutical products at an affordable cost. The statement further asserted that M/s Chemo AG Lugano and the defendant executed a joint venture after obtaining due permissions from Governmental and Drug Control Authorities to conduct research and development of generic drugs. In July 2021, the defendant filed an application to take vacation/modification from the ex-parte ad-interim injunction dated 21st October 2020, passed by the court. The defendant argued that the drug was being used for the sole purpose of research and development. Also, a joint venture had been created between the defendant and M/s Cheo AG Lugano to research to launch the drug in the market after the patent terms expired. The defendant submitted that all the dealings of the defendant were conducted after receiving due permission from the Governmental and Drug Control Authorities and within the scope of patent laws. The defendant relied on judgement of the court in Bayer Corporation v. U.O.I and referred to the section 107A of the Patent Act, to contend that the defendant engaged in sale and export of the drug for the purposes of research and development and activities of the defendant were permissible. The court assessed the situation and arguments and decided to grant permission to the defendant to continue exporting said drug to M/s Cheo AG Lugano and Verben, Sitagliptin under some conditions.

Analysis and conclusion

The judgement granted by the court towards the proceedings is considered appropriate. The plaintiff was unable to prove that drugs being sold by the defendant were being used for commercial purposes. The court opined that the defendant was producing and distributing the drug solely for research purposes. The judgement was passed with some conditions that the defendant will need to satisfy any dealings with the drug in future. The court made it mandatory for the defendant to collect undertaking from the foreign buyers that the drug is being procured for research and development purposes alone and submit along with an affidavit before this court setting out quantities of the drug being exported. Additionally, the defendant will need to submit any information related to the sale of the drug to Government and Drug Control Authorities of India. In our opinion the decision granted by the court clears air for many other companies which might be interested in investing in research and development of already patented products. Also, in the absence of section 107A, the plaintiff would have gained extended exclusivity over the granted patent and denied availability of the cheaper generic drugs in the market soon after the expiry of the patent term.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

A note on foreign filing license requirement in India

Foreign filing license (FFL) is mandatory for person(s), who are resident of India, to apply for patents outside India without first applying in India. The guidelines for same are presented in Section 39 in The Patents Act, 1970. The provision states that a person (Applicant or Inventor) who is a resident of India has to request for an FFL in India if he/she wishes to file a patent outside India without first applying in India. Typically, the Applicants resort to applying for patents directly outside India when the invention does not have a commercial value in the Indian market, or the invention is being considered as a non-patentable subject matter in India. In such cases, a written permission has to be sought from the Indian Patent Office (IPO) for applying for patents outside India.

Section 39 of the Patents Act, 1970 reads:

“Residents not to apply for patents outside India without prior permission

(1) No person resident in India shall, except under the authority of a written permit sought in the manner prescribed and granted by or on behalf of the Controller, make or cause to be made any application outside India for the grant of a patent for an invention unless—

(a) an application for a patent for the same invention has been made in India, not less than six weeks before the application outside India; and

(b) either no direction has been given under sub-section (1) of section 35 in relation to the application in India, or all such directions have been revoked.

(2) The Controller shall dispose of every such application within such period as may be prescribed:

Provided that if the invention is relevant for defense purpose or atomic energy, the Controller shall not grant permit without the prior consent of the Central Government.

(3) This section shall not apply in relation to an invention for which an application for protection has first been filed in a country outside India by a person resident outside India.”

Above mentioned Section 39 applies to the residents of India. It shall be noted that the residential status of the applicant(s)/inventor(s) is considered and not the nationality of the person(s). However, since the term ‘resident’ is not defined in the Patents Act, 1970, we rely upon Section 6 of the Income-tax Act 1961-2017 for defining ‘resident’.

According to Section 6 of the Income-tax Act 1961-2017, an individual is said to be a resident of India:

- Is in India in that year for a period amounting in all to one hundred and eighty-two days or more; or

- Is in India for a period of at least 60 days during the relevant year and at least 365 days during the four years preceding that previous year.

The primary motive behind the foreign filing license requirement is to strengthen the national security. Many defense organizations of the government of India have deemed a few technologies important for military purposes and/or potentially detrimental to the national security if exported. Examples of such technologies may include biological warfare agents, explosives so on and so forth. By receiving a FFL from the IPO, the person(s) ensures that the patent application does not belong to any sensitive matter related to defense or atomic energy.

If the IPO deems the subject matter of the patent application to be sensitive and may endanger the national security of India, the FFL may be denied by the IPO. Many a times, to avoid complications of filing a request or the waiting period, people directly file in the foreign country. What the person(s) needs to understand is that as per the Indian Patents Act, it is mandatory for Indian residents to obtain the FFL to file the patent application outside India and when failed to meet such requirements, as per Sections 40 and 118 of the Patents Act, the person(s) may be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both. Also, the person(s) may face a risk of rejection of subsequent Indian applications.

However, if the person(s) who is a resident of India has filed a patent application in India, then after six weeks from the date of filling of the patent application, the person(s) is allowed to file the same patent application outside India without requiring a written permission from the IPO. The person(s) also need to ensure no secrecy direction has been issued by the IPO for the submitted patent application.

To file for a FFL, Form 25 (Application for permission for filling the patent application outside India) along with complete disclosure of the invention with the reason for submitting such application has to submitted to the India Patent Office.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Patenting nanotechnology inventions – An Indian milieu

The current Indian patent regime fulfils nearly all the requirements of the TRIPS mandate as well as the Patent Cooperation Treaty, 1970. As newer technologies emerge, Science throws challenges after challenges in the path of law. Protection of some of these technologies has grey areas in Indian Patent system. One such technology is “nanotechnology”. Nanotechnology delas with manipulation of nano-metre scale materials. Nanomaterials being building blocks, can be manipulated to create complex materials and devices by regulating shape and size at the “nanoscale”. The broad term “nanotechnology” encapsulates any scientific area or a combination of areas of biology, physics or chemistry, that deals with the manipulation of materials at nanoscale. The significance of nanotechnology is that materials reduced to the nanoscale show very different properties compared to what they show on a macroscale.

Issues faced by Indian’s patent regime:

One of the major concerns with the nanotechnology inventions is it being multi-disciplinary in nature. Such a multi-disciplinary nature of nanotechnology inventions poses challenges for both the patent offices and courts in determining the patentability of nanotechnology inventions. They are faced with the issues of determining which context is appropriate across many disciplines and industries and include all of them in decision making. Additionally, a potential patentee as well as patent office are required to search for prior art not limited to one field but in wide variety of fields.

Another major concern with the multi-disciplinary nature of the nanotechnology inventions is that the corresponding patents bear overly broad claims. In scenario like this, the patentee tries to maximize the profit by preferring patent claims which could cover as many applications and potential markets as possible. Due to presence of high number of such patents with broad and overlapping claims, possibility of fragmentation of patent landscape and patent thickets arises. The broad definition of nanotechnology creates difficulties for both the inventor and the patent examiner in classifying new inventions for patent office purposes. For instance, a patent application may use broad terms, such as “microscale” or “quantum dot” to describe a nanotechnology invention or may use terms like “nano-second”, thereby covering multiple fields. Lack of a standardized terminology for nanotechnology leads to patent overlapping and broad claiming, and due to which both the inventor and the examiner are required to take considerable caution in order to search for prior art in the area, since “nano” alone is not adequate term to search.

According to the Article 27(1) of TRIPS, a valid and enforceable patent can only be obtained on a certain invention if the claims are novel, non-obvious over the prior art and have industrial usage. However, patenting of nanotechnological inventions is not same as that of other technologies and how to contemplate a certain “invention” differs from country to country. In India, under section 2(1)(j) of the Patent Act, 2005, defines an “inventive step” as a feature of an invention that includes “technical advancement” as compared to the existing knowledge that makes the invention non-obvious to person skilled in the art. These provisions were later made stringent by post amendment in 2005, inclusion of Section 3(b) and 3(d) has posed challenges for new technologies in India. Section 3(b) of Indian patent act forms a barrier to nanobiotechnology based patenting due to assumptions about nanotoxicity caused by nanoparticles. Nano biotech inventions causes environmental damage and due to high permeation ability of the nanoparticles further the nanoparticles may get into the bodies of the humans and may result in nanotoxicity. In addition, according to section 3(d), there is vagueness in particle size to be considered patentable subject matter or not. The word “nano” covers inventions of 100nm in size or smaller. In many cases, the nano material may be combination of many particles or technologies or nano particle of an existing material, without substantial difference in character and industrial application. The invention may not pass the “standard efficacy” requirement demanded by Section 3(d). There is a lack of standard for determination of the efficacy and qualification of enhancement of efficacy in India. However, Section 3(d) could be important means to prevent frivolous grant of patents.

Conclusion:

At present, Indian Patent Act has no provision, and no guidelines or regulations has been framed with respect to regulating this technology through TRIPS agreement which in fact encourages protection of intellectual property across all fields of science. This gap between the technology and the patenting of the technology could be attributed to the lack of awareness about the traits and understanding of the technology.

One of the possible solutions to the problem of patenting nanotechnology inventions can be addressed by bringing amendments in the Indian Patent Act. The lawmakers must devise a mechanism to recognize the field of nanotechnology and formulate a comprehensive plan that deals with nanotechnology and patenting of nanotechnology inventions. Since, nanotechnology covers multiple scientific fields, setting up multiple inspections by a team of examiners from different fields instead of a single examiner would aid in better understanding of the claims. Further, a separate database similar to that of traditional knowledge database could be created for nanotechnology. A policy decision is needed for a separate classification for nanotechnology patents. These preliminary steps would surely encourage the research and innovation in the field of nanotechnology which in turn would render prosperity to Indian patenting system.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Parliamentary Standing Committee Recommendations for Expanding the Innovation Ecosystem in India

In an attempt to strengthen the IPR regime in India a comprehensive national IPR policy was adopted in May 2016. Further, a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Commerce was assigned with a task to evaluate the progress achieved at the end of five years since the time the national IPR policy was adopted. The Committee submitted a review report on the Intellectual Property Rights Regime in India after reassessing the Policy to identify the gaps in its implementation and strategize the way forward. In its exhaustive review report, the Committee has recommended ways to incentivize innovations and creativity, strengthen the IPR regime through IP financing, encourage IPRs in agriculture, tribal cures, etc., and ways to protect new and emerging trends in the latest technologies.

Some of the key features identified by the Committee for protecting the overall public interest in innovation are as listed below:

- Economic contribution of IPR.

- Marking published patent applications as ‘Patent Pending’

- Spreading awareness of IPRs across all strata of societies in India.

- Handling Counterfeiting and piracy in a more stringent manner

- Filling up the pending vacancies in the IPR offices to speed up the examination and disposal of IP applications.

- Amending IP related law to address cutting edge technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning.

- Reconsideration of the abolition of the IPAB

- Impact assessment of the Japan PPH model to strategize the way forward for establishing PPH with other countries.

- Encourage IP backed financing in India.

- Amendments to section 3(b) of Indian Patent Act, 1970.

- Reduce the timeline to file an examination report request.

- Provide flexibility in patent law concerning patent abandonment.

- Amendment to Section 104 of the Indian Patent Act, 1970.

- Temporary Compulsory license for IP related to COVID vaccine manufacturing in India.

- Amendments in Form 27 of Indian Patent Act, 1970.

- Use the ‘Thirds Model’ from the Catapult system of UK, for linking academia and industry.

- Communities or individuals exhibiting traditional knowledge must reap the benefits from the IPR regime.

- Encourage IPR in agriculture.

One of the major takeaways from this report is the emphasis on accelerating IP financing. The Committee emphasized that financing in IPR must be encouraged in a comprehensive manner. The Committee has recommended to treat IP as an intangible asset based on which either loans can be provided, or tax exemptions may be made to attract more and more inventors to protect their inventions lawfully.

Also, the Committee has observed that despite adopting a National IPR policy, very little was done on ground in relation to funding for research and development. To address the same the Committee recommended the use of ‘Thirds model,’ that dealt with a ‘Catapult system’ of UK for funding research. The ‘Thirds model’ involves one third of the funding to be from a core grant from the Government, one third of the funding from industry partners and the remaining one third of the funding from a grant from collaborative R&D funds for and by consortia involving Catapults.

Further, the Committee has recommended State governments to extend tax rebates and provide incentives to companies and innovators at the local level on filing of patent and grant additional rewards on the approval of the patents.

Also, the Committee has suggested to label the patent applications that are published as ‘Patent pending’, to acknowledge the credibility of the patent application that in turn would assist the patentee as a marketing tool.

IP Financing in particular, has been observed as the key factor for expanding the IPR ecosystem. Typically, protection of inventions using patents is cost intensive process, wherein the cost includes attorney fees and patent office fees. The high costs involved in patenting inventions is a major hurdle that keeps many small entities from pursuing the IPR. Therefore, financial benefits either by providing incentives, funding for research or by reducing the patent office fees for certain entities like startups, may motivate the entities to protect their innovations using IPR. Further, by easing the affordability of patenting inventions, innovators from different socio-economic backgrounds and different age-groups can be included into the IPR ecosystem.

It is imperative that the Government considers the proposals of the Committee to strengthen the IPR regime and makes changes to the IPR policy to increase the participation in innovation that will result in a fair competition in industrial, economic, social, scientific, and technological spheres.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Can two patents be granted for a single invention – Impact of disclosure of the genus patent over the species patent

In the present case, the Indian Patent office had granted two separate patents for single invention one relating to genus patent IN 205147 (IN 147) and the other patent IN 235625 (IN 625) relating to species patent. The species patent relates to the compound Dapagliflozin, which forms a part of the Markush structure claimed in the genus patent. The defendants argued that two patents cannot be granted for a single invention and allege that the genus patent anticipated the species patent.

Obviousness under section 2(1)(ja)

The Delhi High Court rejected an interim injunction to AstraZeneca as the species patent was obvious, in light of the genus patent as it disclosed the methods to prepare the compound DAPA of the species patent. Although, Example 12 of the genus patent disclosed methods to prepare the compound DAPA with methoxy substitution, a person skilled in the art can replace the methoxy group with ethoxy group to obtain the compound DAPA. Further, there was no technical advancement of the claimed compound compared to the genus or economic significance that would make the synthesis of DAPA an “inventive step” under section 2(1)(ja).

Relevant excerpts from the Delhi High Court’s judgement:

12.7 According to the plaintiff there is no motivation to look at Example 12 when 80 examples have been given of which Examples 1 and 2 were synthesized on a large scale, there is no motivation to change methyl group, there are no teachings towards substitution with ethoxy, efficacy data of Example 12 was not known, the teaching of IN ‟147 were to have hydrogen on central phenyl ring and no ethoxy on the distal phenyl in any of the 80 examples. As noted above, for preparation of the structure in Example 12, four methods have been noted and in the said example though methoxy was used and even though there was no teaching towards ethoxy, there were no teachings even away from ethoxy. Both ethoxy and methoxy being lower alkyl, a person with ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to bring this single change of substitution of methoxy to ethoxy to find out if predictable results ensue. Consequently, this Court is of the prima facie opinion that the suit patent is vulnerable on the grounds of obviousness in view of Example 12 of IN ‟147.

On the contrary, in Natco’s post-grant opposition to Novartis’s Ceritinib patent, IPAB had found that although Ceritinib was encompassed in the Markush structure of the genus patent, the disclosure of the genus patent failed to teach a person skilled in the art to arrive at the specific combination necessary to create Ceritinib. Therefore, the species patent could not be invalidated.

It can be concluded that the description or disclosure of a genus patent may be a game changer for the grant or revocation of the species patent. A species patent for any compound may be granted depending on the details provided in the description of the genus patent.

Double patenting:

Double patenting is not allowable in any jurisdiction. Section 10 (5) of the Indian patent act prohibits patenting of obvious variations of each other in two separate patents, the expiration of the parent patent resulting in an improper extension of the patent rights due to the unexpired second patent.

The court contended that the appellants had filed terminal disclaimer (disclaims the portion of the 20-year term of the second patent that extends beyond the earlier patent’s term) in the USPTO to overcome obviousness type double patenting objection. The appellant had agreed to the validity of US patent equivalent to IN 625 ending on the same day as the validity period of the US patent equivalent to IN 147. The appellants are not entitled to claim different periods of validity for the two patents.

Relevant excerpts from the decision:

We are also of the prima facie view, that once the appellants/plaintiffs, before the USPTO applied for and agreed to the validity period of US patent equivalent of IN 625 ending on the same day as the validity period of the US patent equivalent to IN 147, the appellants/plaintiffs, in this country are not entitled to claim different periods of validity of the two patents.

Conclusion:

In a scenario, where the genus patent discloses the compound of the species patent in its disclosure, such that a person skilled in the art is motivated to arrive at the compound of the species patent, one may consider of filing a divisional application to seek protection for both the genus and species patent. However, the divisional application must be filed before the grant of the parent application. This approach stops any third party from making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing the patented invention for the purpose of using, selling and offering for sale without the approval of the patentee until the expiry of the said patent. Further, the Patent Statute states that a patent issuing on either the original application or a divisional application cannot be employed as a reference against the other. However, if the disclosure of the genus patent fails to motivate the person skilled in the art to arrive at the compound of the species patent, then one may seek protection for genus and the species patent separately.

Further, the patent office also must take utmost care while examining a species patent. Any erroneous decision of the IPO may lead to prolonged litigation process, which could have been avoided, if the applications were examined scrupulously. Such litigation process incurs huge expense for both the parties as well as additional litigation process may burden the court which could have been avoided.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Extension of Limitation period: A Logical Decision in the face of Pandemic by The Supreme Court of India

In the case for “Cognizance for period of Limitation In re in Suo Motu Writ Petition No. 3 of 2020”, the Order dated March 23, 2020, the Supreme Court of India took the ‘suo-moto’ cognizance of the circumstances due to the Covid-19 Virus and its consequences faced by the petitioners across the nation. The limitation period for the order passed on March 23rd, 2020 was effective from March 15, 2020 up to March 14, 2021.

The Honorable Court issued an Order to extend the limitation period with certain restrictions, on March 8, 2021, The Indian Patent Office, abiding by the Order passed by the Honorable Court, extended the limitation period of all pending litigations along with certain norms, based on the observation that the country was slowly returning to normalcy. The Controller General of Patents, designs and Trademarks issued a notice elaborating that:

- The cases whose limitation periods had expired during the period between March 15, 2020 and March 14, 2021, will have an extended period of 90 days. However, if the actual balance period is beyond 90 days, the longer period will apply.

- Further the period from March 15, 2020 to March 14, 2021 shall remain excluded in computing the limitation period for the pending cases in the above mentioned time frame.

However, due to a sudden surge in the number of Covid patients and Covid related deaths in the country, a writ petition was filed April 22, 2021. Due to the unprecedented high intensity of the second wave of Covid in India, the Hon’ble Court took into consideration the difficulties encountered by the petitioners for filing petitions/suits/applications/appeals or completing any other proceedings within the limited period as prescribed under the Law, and extended the corresponding period of limitation. This petition was taken up Suo moto for hearing by the Supreme Court.

The Honorable Court reconsidered the order passed on March 08, 2021, and passed an Order on April 27, 2021. The Supreme Court took suo-moto cognizance of the second wave of COVID situation in the country, based on the provisions laid out in the article 141 and 142 of the Constitution of India. The Article 142(1) states: “The Supreme Court in the exercise of its jurisdiction may pass such decree or make such order as is necessary for doing complete justice in any cause or matter pending before it, and any decree so passed or order so made shall be enforceable throughout the territory of India in such manner as may be prescribed by or under any law made by Parliament.” (Emphasis added). The Article emphasizes that the Supreme Court has the power to issue orders to rectify the shortcomings in the statute based on the circumstances, so as to provide “complete justice” in any matter pending before it. And the Article 141 implies that the law declared by the Supreme Court is applicable to all courts in India until further orders are issued.

Accordingly, in the order dated April 27, 2021, in continuation to the order dated 8th March, 2021, the Supreme Court extended the limitation of all judicial or quasi-judicial proceedings until further orders. Further, the Honorable Court clarified that the period from 14th March, 2021 onwards shall be excluded for computing the periods for various proceedings, till further orders are issued.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

- « Previous Page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- …

- 84

- Next Page »

Follow

Follow