Patenting food recipes in India

The most obvious question is whether patent of food is possible. Yes, of course, you can patent your unique recipe. However, there are certain things which the patentee needs to bear in mind before applying for a patent for his/her food recipes. The patent application for the food recipe needs to be drafted carefully. For a patent application to get granted, the food recipe will need to satisfy three requirements: Novelty, Non-obviousness, and Industrial Applicability. Additionally, the food recipe cannot be a “mere admixture of substances resulting in aggregation of properties of the components” according to Section 3(e) of The Patents Act.

The food recipe patent can be drafted to either claim the process or the composition(ingredients) used to make the food item. In India process claims have higher acceptance rate. The process to make the food recipe including steps such as baking, heating, stirring, grinding and so on, if found novel and inventive, then there is a higher chance of acceptance. If there is a novel step involved which results in the increase in the shelf life or provides nutritional benefits, claiming the same can improve the chances of getting a patent grant. For instance, a procedure of preserving food products to disable the microorganisms in food products by enabling an edible phenolic compound in food and the outcome is subjected to the high-pressure conditions.

Let’s consider an example of an already granted patent in India, “Preparing a sugar free bread [Application no 483/DEL/2004]. Although the process to prepare a bread is well-known and obvious to anyone skilled in the field, the granted patent deals with mixing of few ingredients which result in a Sugar Free bread. The application focused mainly on illustrating the preparation through process claims.

From above information we can clearly summarize that drafting of the patent plays a key role in food-based patent applications. Standards such as ingredients, proportions, mixing or cooking time should be kept as broad as possible to discourage potential competition from writing around the claims with small variations. For example, if you are mixing sugar in your recipe, then claiming the ingredient as sweetener (which might include honey, corn syrup etc) rather than as sugar will provide much wider protection to the food patent. Another thing to keep in mind is that the ranges claimed should not only safeguard your invention but also not be broad enough to violate another’s patented recipe. Additionally, if in case your recipe doesn’t satisfy the requirements to be patented, don’t get discouraged, there is always an alternative available. You can go ahead and include that recipe in a book or magazine and obtain copyrights for the recipe or you can always keep the recipe as a trade secret and prevents others from copying your recipe.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

The convergence between Blockchain technology And Intellectual Property Rights

Introduction

Blockchain is an evolving technology which enables stakeholders to protect information exchange in sophisticated ways. With the onset of lockdowns due to Covid, work from home has become the new norm. This shift in paradigm calls for innovative methods to share valuable data without being tampered in any manner. Blockchain has the potential to transform interactions between multiple industries to be more transparent and secure thus attracting financial players into investing in the technology. For example, blockchain that started as a secured technology for cryptocurrencies has now found application across various industries like healthcare, education, travel businesses so on and so forth. The cryptographic security of data provided by blockchain technology has caught the attention of C-suite executives that implies that most companies are currently patenting inventions involving blockchain technology.

Features of blockchain technology

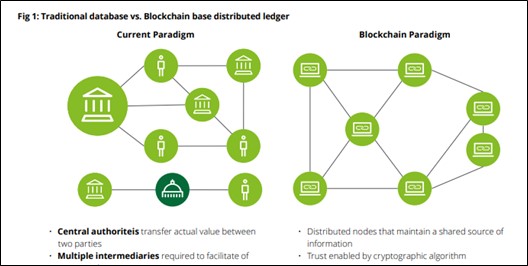

A blockchain is a distributed ledger that records transactions in real – time. However, the transactions are secured by obtaining the consensus of the respective participants thus managing any manipulations or errors that may occur while maintaining the data quality.

Source: PoV_Blockchain_Media_interaktiv.indd (deloitte.com)

The main features of a blockchain include:

- Providing a unified platform for all transactions involved between various nodes of the blockchain.

- Ensuring transparency between customers and regulators across the various industries involved.

- Helping in substantial cost reduction for the overall transaction process.

Patenting blockchain inventions

In patent regime, blockchain technology broadly falls under the category of software inventions. Therefore, in India, the relevant objections for blockchain related patents are likened to those that may appear for software patents since they include application software and cryptography. Accordingly, the most frequently occurring objection is with respect to section 3(k) of the Indian Patents Act, because the blockchain is mainly a database ledger. In accordance with the section 3(k), the use of database along with AI may be considered as either an algorithm or a computer program per se. However, if the inventor is capable of indicating a technical advancement in using a tangible product by the use of blockchain technology in combination with AI, then such inventions can be patented.

Blockchain technology for management of ip

The application of blockchain in combination with AI in the recent years has influenced the IP ecosystem drastically. The application is helping companies on various grounds that may include:

- Identifying lucrative opportunities in the marketplace sans the potential commercial risks by summarising the overall patents available in any sphere of interest at a faster and more cost-effective manner,

- Establishing clear ownership rights especially in proving infringement for abstract works like music or dance for which IP rights are not registered immediately at the time of creation in the current framework,

- Licensing trademark rights through smart contracts and

- Assisting in counterfeit reduction by verifying the products’ origin based on unique identifiers.

Thus, the combined use of blockchain and AI in the IP ecosystem can streamline IP transactions with respect to authentication and verification in copyrights, trademarks and patent areas. Also, companies are now using this technology to reduce the number of patent infringement lawsuits against them.

Conclusion

In the recent years, the Government of India has laid a number of initiatives on Blockchain for digitizing Indian economy. In pursuit, the NITI Aayog has been exploring a platform called ‘IndiaChain’ – a blockchain enabled infrastructure for Indian enterprise and government.

Further, the Indian Patent Office has announced a tender for ‘Expression of Interest for Making use of Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain’ at the IPO, for easing patent search and analysis. The AI engine requires to learn before implementing a given task. But since patents are techno-legal documents, the AI engine has to store data related to law as well as technical information related to every field of study that can be patented. Therefore, each AI engine may be designed to store data related to each class of patents, for example electronics.

In view of the plethora of knowledge and information available, innovations that use AI with blockchain to ease the access to any particular data with precision and at minimum possible time is the need of the hour. This can help accelerate the rate at which discoveries happen in the near future.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Revocation of registration of potato variety FL 2027 held by Pepsico India and its impact

Background

Lays potato chips, a product of Pepsico, uses FL-2027 variety of potatoes which was introduced in 2009 in India. It came into limelight in April 2019, when Pepsico filed infringement cases against farmers in Gujarat and alleged that nine farmers who are growing and selling this variety in Gujarat are not part of its “collaborative farming programme”. Additionally, filed a lawsuit of Rs.4.2 Cr against four small farmers under the Act. However, widespread protest and boycott threats by political parties and farmers groups, forced Gujarat government to step in and this forced Pepsico to withdraw all cases in May 2019. Following which Ms. Kuruganti filed an application to revoke Pepsico’s registration in June 2019 on the grounds of being against the public interest.

Summary of the final judgement by PPV&FV

On Dec 03, 2021, PPV&FV revoked the registration of potato variety FL 2027 registered in favor of Pepsico India Holdings Private Limited. The revocation application submitted was mainly based on the grounds of providing incorrect information by the applicant, certificate of registration is not valid and that the grant of certificate of registration is not in the public interest. Based on the arguments submitted by the defendant and the facts, on December 03, 2021, the registration of FL 2027 was revoked under Sections 34 (a), (b), (c), and (h) of PPV&FR Act, 2001. Additionally, the registrar was asked to develop a standardized sheet for evaluation of application for registration of plant varieties in accordance with Act, Rules and Regulations.

Opinion

Revocation of the registration certainly made the farmers of India happier, as it allowed them to buy or sell FL 2027, a variety of potato without being the member of the “collaborative farming programme”. This decision as such, if misunderstood, could deter many of the large entities from entering India who might want to bring in new varieties of plants. In this case, the PPV&FR revoked the registration only after it was proven that the defendant may not have submitted all the documents as per the requirements, even after being requested. As alleged in the Revocation Application, it was found that Dr. Robert W Hoopes, who is the breeder of FL 2027, has not validly assigned it to the Assignee (Recot Inc subsequently name changed to Frito-Lay North America (FLNA)). Additionally, it was pointed out that several farmers were put to hardship including the looming possibility of having to pay huge penalty on the purported infringement they were supposed to have been committing which did not eventually happen as on date.

Considering the facts of the case and the evidence, it is evident that the registration of potato variety FL 2027 registered in favor of Pepsico India Holdings Private Limited was revoked as a result of negligence or intentionally trying to mislead the authorities in India. We are of the opinion that after the creation of the standardized sheet by the registrar, instances such as this could be reduced to a large extant. Additionally, this will help the future applicants with easier and streamlined process for registration of their plant variety and will avoid any complications that may arise in future as happened in case of the registration of potato variety FL 2027.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Can the Indian patent office restrict the examination to certain set of claims?

A patent application is queued for examination once the request for examination has been made in the prescribed manner under sub-section (1) or sub-section (3) of section 11B. During the examination, the Patent office examines the patent application and issues a first examination report (FER), which is communicated to the Applicant. The objection raised in the FER may be with respect to novelty, inventive step, sufficiency of disclosure, formal requirements and unity of invention, among others.

The IPAB on its order dated 27th October 2020, had set aside the impugned order of the respondent (THE CONTROLLER OF PATENTS) against the patent application numbered 531/DELNP/2013 (hereinafter referred to as “the Current application”) and granted a patent to the applicant (UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN). During examination of the current application, Examiner had raised objection that the claims lack unity of invention under section 10(5) and additionally restricted the examination to only a chosen set of claims. Section 10(5) of the Indian patent act mandates that a single patent application should relate to single invention or to a group of inventions linked so as to form a single inventive concept.

Fact of the case

A National phase application numbered 531/DELNP/2013 based on the PCT International application was filed by the applicant. A first examination report (FER) was issued on 02 July, 2018. One of the objections communicated in FER are as follows:

“In view of the plurality of distinct inventions (see Para under heading- Unity of invention), the search and examination u/s 12 and 13 of the Patents Act, 1970 (as amended) has been deferred with respect to groups of inventions II to VII containing claims 22 to 28. Hence, present examination report is restricted to Invention I having claims 1-21 only.”

Further, a hearing was conducted and the Appellant filed written arguments along with amended set of claims at the Patent Office within the stipulated time. An impugned order was issued by the respondent on 06 March, 2020.

IPAB’S DECISION

Therefore, while the objection with regard to ‘unity of invention’ can well be taken if the plurality of invention is found to have been claimed but restricting the examination to any chosen set of claims by the Controller is not mandated by the Patents Act,1970, particularly so when the fee in respect of examination of all the claims are paid by the applicant.

A review of the International Search Report in respect of this application in International Phase, we notice that International Seraching Authority (ISA) has found the lack of “unity of invention” and searched only the first set of claims i.e. claims 1-21. Further, ISA objections on ‘Unity of Invention” are verbatim matching with that raised by the learned Controller in the instant application.

CONCLUSION:

During the examination of the patent application, the search and examination of all the claims has to be carried out irrespective of the fact whether the patent application relates to a plurality of invention. The Controller may raise objection for lack of unity of invention under section 10(5) and instruct the Applicant to elect the set of claims the Applicant desires to retain and subsequently file a divisional application for the other set of claims. However, in practice the Controller restricts the search and examination to chosen set of claims without any intimation to the Applicant. Moreover, the examination report issued should not be a verbatim matching with search report issued by the other patent office as the patent law varies for each jurisdiction. For example, the WIPO conducts a search for only first set of claims, as the ISA (International search Authority) is under no obligation to examine the multiple set of claims once a single fee is paid. They intimate the same to the Applicant and conduct a further search on receipt of the corresponding fee. On the other hand, the India Patent Act and Rules mandates to examine all the claims as the fee for all the claims are paid prior to issuance of the FER and forbids the examination of selected set of claims as per the convenience of the Controller.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Term of a patent in India and Strategies to reap maximum benefits from the patent term

What is a Patent?

In basic terms, Patent is a set of exclusive rights granted by a country to an applicant in exchange for a public disclosure of their invention. The invention could be a product or a method/process which provides a technical solution to a problem or offers a new way of doing something. The “exclusive rights” granted to the applicant that include the rights to exclude others from making using, selling, importing, or distributing the patented invention without the permission of the patentee.

Types of Patent Applications

In India, Patent applications can be broadly classified into 3 types based on the approach taken by an applicant for filing a patent application in India viz.,

- Ordinary application

- Convention application

- PCT National phase application

A much detailed explanation of the types and filing of different types of patents applications in India can be read here.

Term of a Patent

Section 53(1) of The Patents Act 1970 sheds light on the term of patents. Term of patent is a period of time during which the applicant is awarded exclusive rights to exclude others from infringing i.e., making, using, selling, importing, or distributing the patented invention without the permission of the applicant. The set of exclusive rights for a patent is granted to an applicant for a limited period of time, which is 20 years. The patentee will have the exclusive rights to exclude others from making, using, selling, importing, or distributing the patented invention for a period of those 20 years. However, once the term of the patent is completed, the patent is termed expired, implying that the patented invention can now be made, used, sold, imported, or distributed by anyone without needing the permission of the patentee.

During the term of the patent i.e., 20 years (assuming the patent is active), the patentee can have a monopoly in the market over the patented product by stopping others from commercially exploiting the patent or can license the patent to other entities. The patentee can also claim damages from entities that infringe upon the patent, however, can only claim damages for infringements that might have occurred after the date of publication of the application until the expiry of the patent. This is where the term of a patent plays a vital role.

The term of a patent is a fixed 20 year term, however, calculation of start of the term of a patent may change based on the approach of an applicant in filing a patent application in India. Calculation of start of the patent term (considering just the 3 types of applications mentioned in the foregoing) is different in two scenarios, one in case of Ordinary application and one in case of Convention application or PCT National phase application.

Ordinary Application

In case of an Ordinary application, the patent term starts from the earliest priority date. In a scenario where a provisional application is filed followed by a complete application within the 12 months due date, the date of filing the provisional application (one with earliest priority date) is considered for calculating the term of the patent. For example, assuming a provisional application being filed on January 01, 2000 followed by a complete application filed on January 01, 2001. Assuming that a request for early publication was field using Form 9 on January 01, 2001 along with the complete application, the application may be published within 2 weeks from the date of filing the request (January 15, 2001 will be assumed as the date of publication for further explanation). The application may then be prosecuted and may be granted. In the instant case, the term of the patent is considered from the earliest priority date i.e., date of filing the provisional application. The expiry of the instant patent application will be on January 01, 2020.

Now, since the application was published on January 15, 2001, the patentee has the right to claim damages, if any, from entities infringing on the patent from January 15, 2001 until the expiry of the patent.

Convention application/PCT National phase Application

In case of Convention application, an application (provisional/complete) may be first filed in a convention country and then enter India within 12 months from the earliest priority date of the convention application. In this case the date of filing the application in India is considered for calculating the term of the patent. For example, assuming a provisional application being filed on January 01, 2000 in a convention country followed by a complete application in India filed on January 01, 2001. Now, similar to the ordinary application, assuming that a request for early publication was field using Form 9 on January 01, 2001 along with the complete application, the application may be published within 2 weeks from the date of filing the request (January 15, 2001 will be assumed as the date of publication for further explanation). The application may then be prosecuted and may be granted. In the instant case, the term of the patent is considered from the date of filing the application in India i.e., date of filing the complete application in India which is January 01, 2001 in the instant case. Therefore, the expiry of the instant patent application will be on January 01, 2021.

Similarly, in case of PCT National phase Application, a provisional application is filed in any of the PCT member country including India, and then file a PCT application within 12 months from the earliest priority date, the date of filing the PCT application is considered for calculating the term of the patent. For example, assuming a provisional application being filed on January 01, 2000 in any PCT member country followed by a PCT application filed on January 01, 2001 simultaneously entering India on the same date. Now, similar to the ordinary application, assuming that a request for early publication was field using Form 9 on January 01, 2001 along with the complete application, the application may be published within 2 weeks from the date of filing the request (January 15, 2001 will be assumed as the date of publication for further explanation). The term of the patent in this case is considered from the date of filing the PCT application which is January 01, 2001 in the instant case. Therefore, the expiry of the instant patent application will be on January 01, 2021.

In view of the two scenarios explained in the foregoing viz., the Convention application and the PCT National phase application, since the term of the patent expires on January 01, 2021 and not on January 01, 2020 as in case of an Ordinary application, and also that the applications in case of Convention and PCT National phase were published on January 15, 2001, the patentee has the right to claim damages, if any, from entities infringing on the patent from January 15, 2001 until the expiry of the patent, which is January 01, 2021 thereby giving the patentee an extended period of protection (which is almost one year in this case) as compared to the Ordinary application filing route.

Strategies for availing maximum benefits from an Indian patent by an Indian applicant

Strategy 1: Ordinary application

An Indian applicant can directly file a complete application instead of filing a provisional application first, and then request for early publication. In this case the application may be published within two weeks from the date of such request. Now, in case of the patent grant, the term of the patent is calculated from the earliest priority date (i.e., date of filing complete application in this case), and since the application was published within two weeks from the date of filing the complete application, the patentee can claim damages from the date of publication of the application. However, in such cases, the applicant is deprived of the 12 months term between the earliest priority date and the date of filing a complete application, as the applicant now directly files a complete application. The patent, in the instant case, effectively expires 20 years from the earliest priority date.

Strategy 2: PCT National phase

An applicant can benefit the most by utilizing the PCT National phase or the convention route. An Indian applicant can avail the benefits by opting for a PCT application, wherein the applicant can first file a provisional application in India followed by a PCT application within 12 months from the earliest priority date, and simultaneously entering India. In such case, the term of the patent is calculated from the international filing date, and for the purpose of examination, prior arts with priority date falling before the earliest priority date are considered. In this way the applicant can avail the most from the patent.

Having said that, the costs incurred in filing an application via PCT national phase route is higher as compared to that of filing an Ordinary application. However, if the applicant believes that the invention is commercially viable, the applicant can opt for the PCT, as the outcome of having the shift in the term of patent protection can outweigh the costs incurred during the filing of such patent applications. On the contrary, this approach may be a hurdle for individual inventors or small companies that are not financial backed and therefore opting the PCT route may not be affordable.

Strategy 3: Convention route

An Indian applicant can directly file an application in any of the Convention country by requesting permission for foreign filing (Form 25), and then entering India within the 12 months deadline. In the instant case too, as discussed in the foregoing, the term of the patent is calculated from the date of filing the application in India, whereas for the purpose of examination prior arts with priority date falling before the earliest priority date are considered.

In case of PCT or Convention application, the patent expires effectively by a maximum of 21 years from the earliest priority date.

Conclusion

In view of the scenarios discussed, it is clear that the applicant benefits the most by opting a PCT route or a Convention route. In fields especially like pharma, where the competition is fierce and the patents play a vital role, just the approach of filing a patent application makes a significant difference. In the PCT and the Convention route, the term of the patent is shifted by almost a year as the term of patent is calculated from the date of international filing/date of filing in India, thereby giving the applicant an edge over opting Ordinary application filing. Having said that, in case of Ordinary application, if the applicant believes that the invention requires no further development, it is advisable for an applicant to directly file a complete application, followed immediately with a request for early publication to avail maximum benefits from the patent.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

IPR filling statistics in India 2020: Summary

In spite of the COVID-19 pandemic, inventors around the world have managed to file almost 3.3 million patent applications in 2020 which represents an increase of 1.6% over 2019 filings. A significant rise in filings was contributed mainly by China which filed 96,498 more applications than in 2019 combined along with contributions from the Republic of Korea (7,784), China, Hong Kong SAR (5,024) and India (3,144). The overall trend to date is upwards, applications having increased from approximately 1 million in 1995 to around 2 million by 2010 and reaching the 3 million mark in 2016. Applications received at offices located in Asia represented 66.6% of the world total, 2.2 million applications approximately.

The size and structure of the economies, population, gross domestic product (GDP), research and development spending are some of the variables which might provide us more information regarding the variations in the patenting activity across countries when resident patent activity with regards to variables mentioned. With 8,249 resident patent applications per unit of USD 100 billion GDP, the Republic of Korea filled most patent applications in 2020. Followed by China (5,845), Japan (4,696), Germany (1,609) and Switzerland (1,605). India (274) was awarded 25th spot.

From the 2019 data, computer technology was the most frequently featured technology in published patent applications worldwide with 284,146 published applications. Followed by electrical machinery (210,429), measurement (182,612), digital communication (155,011), and medical technology (154,706). Between 2017 and 2019, China (8.6% of all published applications), the U.K. (7.5%) and the U.S. (11.8%) filed most heavily in computer technology. As for India, 17.8% of total published applications were related to pharmaceuticals.

In 2020, approximately 1.6 million patents were granted worldwide which is an increase of 6% over 2019. Highest number of patents in 2020 were issued by China (530,127), followed by the U.S. (351,993), Japan (179,383), the Republic of Korea (134,766) and the EPO (133,706). India granted 26,361 patents which resulted in a growth of 11.8% patents granted in 2020. Both resident and non-resident grants contributed equally to total growth in India.

Another statistic worth noting is the average age of patents in force in 2020. For the 92 offices for which the data was reported, around 41.3% of patents granted remained in force for atleast 7 years after the filing date and about 18.9% lasted the full 20-year term. India reported 12 years as average age of all patents in force. On the other hand, percentage of rejected applications with respect to the total were highest in China (35.5%), the Republic of Korea (26.7%) and the U.S. (45.2). The proportion of withdrawn or abandoned applications was greatest in Brazil (57.8%), Germany (38.3%) and India (37.7%). When it comes to pending applications, China and the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) had almost 1 million pending applications. India had almost 117,336 applications still pending in 2020, which had sharply reduced compared to a year earlier by 23.4%.

International patent applications filed via WIPO’s PCT reached 275,900 applications in 2020. China with +16.1% was the only country that recorded a double-digit annual growth between 2019 and 2020, whereas India reported a -6.5% decline over the same period.

We are of the opinion that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, a rise in filing of patents in India sheds light on the effort being put in by the government to educate and encourage people regarding patents. Government has significantly reduced the filing fees for natural persons, small entities, and educational institutions to encourage patent filling. Additionally, to encourage women, government of India has provided relaxations such expediated examination and so on. Factors mentioned above contributed to the significant growth in filing of patent applications in India in our opinion. In coming years, we also anticipate that government will keep taking steps to encourage people to file for patents as it will encourage innovation, cheaper products, and ultimately will improve the economy.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Updated tax rates for transfer or permitting the use of Intellectual Property rights in India

On 30th September, 2021 by issuance of Notification No. 06 /2021- Central Tax (Rate) by the Ministry of Finance of India. The notification made the following amendments to the notification of the Government of India, in the Ministry of Finance (Department of Revenue) No.11/2017- Central Tax (Rate), dated the 28th June, 2017, published in the Gazette of India, Extraordinary, Part II, Section 3, Sub-section (i), vide number G.S.R. 690(E), dated the 28th June, 2017:

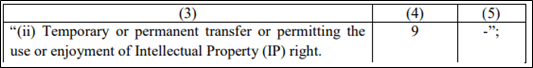

(i) in the Table, –

(b) in serial number 17, –

(A)item (i) and the entries relating thereto in columns (3), (4) and (5) shall be omitted;

(B) for item (ii) and the entries relating thereto in columns (3), (4) and (5), the following entries shall be substituted, namely:-

In this notification, Ministry of Finance of India, increased the Central Goods and Services Tax (CGST) levied on IP from 6% to 9%. Following which the state governments released a notification updating the State Goods and Services Tax (SGST) levied on IP from 6% to 9%. This as a result increased the overall GST levied on temporary or permanent transfer or permitting the use of enjoyment of Intellectual Property (IP) right, from 12% to 18%. Additionally, the notification amended the GST rate levied on IP’s not relating to Information Technology (IT) software from 6% to 9% which is now same as GST rate levied on IP’s relating to IT software. This amendment addresses the questions/issues that were encountered while categorizing and calculating fees to be paid for certain inventions nearly relating to IT software while dominated by concepts and components relating to other disciplines.

On 27th October, 2021 by issuance of Notification No. 13/2021- Central Tax (Rate) by the Ministry of Finance of India. The notification made the following amendments to the notification of the Government of India, in the Ministry of Finance (Department of Revenue), No.1/2017-Central Tax (Rate), dated the 28th June, 2017:

(b) in Schedule III – 9%, against S. No. 452P, in column (3), the words “in respect of Information Technology software” shall be omitted.

On 27th October, 2021 by issuance of Notification No. 13/2021- Integrated Tax (Rate) by the Ministry of Finance of India. The notification made the following amendments to the notification of the Government of India in the Ministry of Finance (Department of Revenue), No.1/2017-Integrated Tax (Rate), dated the 28th June, 2017:

(b) in Schedule III – 18%, against S. No. 452P, in column (3), the words “in respect of Information Technology software” shall be omitted

By way of all these notifications, Ministry of Finance of India, increased the Integrated GST (IGST), which includes both central and state tax rates, levied on any “Temporary or permanent transfer or permitting the use or enjoyment of Intellectual Property (IP) right” from 12% to 18%. This change will make the GST levied on IP’s not relating to IT software same as the GST levied on IP’s relating to IT software. This amendment undeniably increases the financial burden on the IP owner, which in turn might discourage an inventor with lesser financial resources available at his/her disposal. Also, it needs to be pointed out for the sake of simplicity here that these changes to IGST rates relating to IP’s is applicable to any kind of temporary, permanent transfer, or renting, or leasing the IP to someone else.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Patent pool as a tool to tackle COVID-19 Pandemic

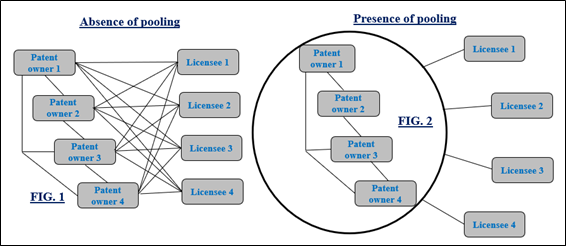

No wonder, innovation steers today’s world. In many instances, several enterprises develop technologies that end up overlapping in various aspects. In scenarios like these, possibilities of one technology to infringe on other technologies is well likely to arise. To address this, patent pools were created. According to WIPO, patent pool is defined as “agreement between multiple patent owners for licensing their patents to one another or any other third party for the purpose of sharing their intellectual property rights.” In the absence of a patent pool (FIG. 1), each of the licensee must negotiate with all the patent owners for obtaining license, which is time consuming and expensive process. Contrastingly, in the presence (FIG. 2), licensees can avail the patent rights as one package from the pool resulting in simplification and cutting down transaction costs.

For a patent pool to work, it requires most key patent holders to be in the pool. As long as members holding the IP positions are participating to ensure that patent pool gains “critical mass” and it is well administered, patent pool will work, otherwise it will fail. The first patent pool was established in mid 1850s and, gained momentum in 2000s when the USPTO encouraged creation of patent pools for biotechnology patents to combat concerns governing biotechnology patents. In the years 2000-2005, discussions on establishing a patent pool began due to SARS outbreak, during which several corporates had filed patent applications on the “genomic sequence” of the virus that was responsible for the outbreak.

Amidst the pandemic COVID-19- Pooling

In 2020, the pandemic COVID-19 has shown benefits of collaborative research in many ways. The TRIPS agreement allows countries to grant compulsory licenses to companies to produce a patented product at times of emergencies. In view of this, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Union strongly supported patent pooling, whereas the US and UK were against the patent pooling for pharmaceutical drugs in the 73rd World Health Assembly held virtually on 18-19th May 2020. At the World Health Assembly, Costa Rica suggested pooling of rights to deal with pandemic through free or affordable licensing to ensure the outputs from the efforts could be used by countries with limited economic resources to deal with the issue. This proposal received recognition from all over the globe, except US and UK. Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, Medicine Patent Pool (MPP) has been actively aiding in removing any IP-related barriers. MPP is a United Nations international organization founded in July 2010, by Unitaid. It is a global health initiative that collaborates with potential partners to make medical innovations to diagnose and treat major diseases in low-and-middle income countries and negotiate agreements with pharmaceutical companies. MPP has been mustering information pertaining to medical patents for COVID-related patents. It seeks voluntary licenses from the patent holders of anti-retroviral drugs to form pooled resource of patented innovations. Through this initiative, pharmaceutical companies and innovators can access the pooled patent rights to develop the new and adapted innovations required for sale in developing countries. The trouble and expense of negotiating licenses where several patent holders might hold rights in a single innovation can be mitigated. Patent holders are benefitted by receiving royalty from various countries and a collaborative platform for easy access to develop the need, as the price of licensing the already patented technology to develop new medicines can be brought down by patent pools.

MPP has created various online databases such as MedsPaL for patents relating to medicines such as remdesivir, tocilizumab and VaxPaL specifically for patents related to COVID-19 vaccines. Another commendable initiative is taken by the WHO, by creation of a voluntary patent pool known as COVID-19 technology access pool (C-TAP), led by Costa Rica and WHO. The goal of C-TAP patent pool is to bundle multiple pieces of IP together to reduce the transaction costs of knowledge sharing on a patent-to-patent basis. MPP is regularly updating its patent intelligence database, MedsPaL, with the status of products during COVID-19 and will continue to update as and when the new patents emerge to find the cure during the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, Remdesivir, Lopinvir/Ritonavir, Favipiravir, Tocilizumab and Sarilumab have been updated in the database.

Patent pooling: India’s perspective

Patent pooling is recent concept in India. The Indian Patent Act, 1970 neither provides for nor obstruct the creation of patent pools. Nonetheless, one could consider Sections 68, 69 and 102 from Patent Act, 1970 to avail patent pooling with terms and conditions making such relaying legally valid. However, there are issues pertaining to conflicts between the Competition Act, 2002 and Patent Pooling, as the said Act disallows any types of agreements or licenses which have an adverse effect on fair competition in India. With respect to Indian scenario, the Competition Act, 2002 prohibits various IPR licensing agreements that are calculated to be of anti-competitive natured. When such a conundrum arises, Section 140 of the Indian Patent Act defines certain conditions to be considered while getting into a licensing agreement in relation to licensing of a patented article. Hence, it can be contemplated that the Patent Act, 1970 has certain provisions to address the issues coming out of patent pools. The idea of a patent pool particularly may be useful for a generic drug manufacturing major like India. The pool can help with faster production of drugs which are found to be effective for the pandemic. Recently, one Indian generic drug manufacturer Aurobindo Pharma Limited joined the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) to manufacture several anti-retroviral medicines. This step would facilitate Aurobindo Pharma to have access to the patented drugs of “Gilead Sciences” which was recently introduced into the pool.

Conclusion:

Patent pools can be highly beneficial for facilitating innovation, accelerating the development of a medicine for COVID-19, specially amidst the outbreak. It will be a win-win situation as the patent holders will receive royalties for their innovations, thereby maintaining their income while the low-and middle-income countries would get access to the much-needed medications at affordable prices. For the generic drug manufacturing companies like India, the companies can combine different medications into singe/fixed doses to create better medicines. As in, back in 2014, ViiV Healthcare contributed to MPP by providing dolutegravir, an antiretroviral drug for HIV to its pool resource. It allowed generic drug manufacturing companies to create an affordable version of anti-HIV drug. In India, for the development of commerce, the knowledge regarding the concept of patent pooling should be known to every inventor so as to get good progress in the field of technology or pharmaceuticals. Creation of pandemic patent pool at a global level to pool innovations is good to promote access to medicines and protect public health in large scale.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Does AI qualify as an ‘Inventor’ based the statute in Indian Patents Act, 1970?

Human Intelligence is the ability of a human brain to recognize and interpret information and enhance the existing knowledge based on its understanding capabilities. In a pursuit to create a working replica of the human brain, the scientists came up with ‘Artificial Intelligence’ on electronic devices.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is used to automate machines to perform tasks that usually require human intervention. The domain of AI includes finding new utilities in terms of visual perception, translation, speech recognition, decision – making based on available database, etc.,

When it comes to intelligence, we have certain laws that protects an individual’s tangible ideas as Intellectual Property. In India, we have the Indian Patents Act, 1970, that lays the rules and regulations for providing Intellectual property rights for the inventors of new and innovative inventions.

With the advancements in the technology, the AI is now capable of rendering new ideas that are tangible and worthy of being patentable. However, the question is whether our current law recognizes AI as an inventor and what are the pros and cons of recognizing an AI as an inventor. We will be addressing the same from the Indian Patent Law perspective.

Currently, Indian Patents Act does not specifically define the term ‘inventor’. Therefore, it becomes even more necessary to understand the Indian Patent Act as a whole, to apprehend the objective of the legislator and comprehend the term ‘inventor’.

In a recent application numbered 202017019068, the Controller has objected to recognizing AI as an inventor citing the provisions laid in Section 2 and Section 6 of The Indian Patents Act, 1970 (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Act”). The two sections elaborate on the criteria for recognizing an inventor and the ‘person’ who can apply for a patent in the Indian jurisdiction. In particular, Section 6 provides information about who can apply for a patent. Section 2(1)(s) defines those who can be referred to as a ‘Person’ while Section 2(1)(y) defines who is not a true and first inventor. The definitions of these relevant sections as specified in the Act are as follows:

Section 6(1)(a): ‘An application for a patent for an invention can be made by any ‘Person’ claiming to be the first and true inventor of the invention.’

Section 2(1)(y): "true and first inventor" does not include either the first importer of an invention into India, or a person to whom an invention is first communicated from outside India.

Section 2(1)(s): ‘In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires, — “person” includes the Government’.

It is important to note that the ‘Person’ must claim to be the first and true inventor of the invention. Unlike copyrights, the ‘Person’ does not naturally become the first and true inventor of the invention until they claim to be so.

It may be noted that in accordance with the Section 2(1) (s) the reference to ‘Person’ in the Act may be either a natural person or the Government. However, it is interesting to note that the term ‘person’ does not just consist of any natural person and/or Government but it includes the reference to Government along with other entities who can be the true and first inventor of the invention. This means that anybody or anything that is the first and true inventor of the invention can be the ‘person’ eligible to claim to be the inventor of the invention for which a patent is being claimed.

Although Section 2(1)(y) mentions about who cannot be an inventor, an ambiguity arises with respect to who can be called the true and first inventor for the invention when an AI is the true and first inventor of the invention. Therefore, to understand who exactly qualifies to be an inventor in India, we need to look into certain Indian case law judgements in combination with the Act.

One of the Indian case laws: V.B. Mohammed Ibrahim v. Alfred Schafranek, AIR 1960 Mysore 173 sets precedence with regard to inventorship. In accordance, it was held that a financing partner could not be treated as an inventor, nor can a corporation be the sole applicant claiming itself as the inventor. This judgment emphasizes on the fact that mostly a natural person (who is neither a financing partner nor a corporation) who genuinely contributes their skill or technical knowledge towards construing the invention, qualify to be claim the inventorship.

However, it might be argued that an AI may also contribute its skill or technical knowledge for an invention to qualify as an inventor. To address the same, we need to look into another Indian case law: Som Prakash Rekhi vs Union Of India & Anr on 13 November 1980 AIR 1981 SC 212, wherein the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India passed a judgement regarding who can qualify as a legal ‘person’ according to Indian judicature. Accordingly, the judgment held that a jurisdictional person is the one to whom the Law attributes ‘personality’. When we refer to a juristic personality, we refer to a legal entity who have the rights to sue or who can be sued by another entity. Inherently, an AI does not have the capability to use the numerous rights, nor can it perform the required duties of any juristic personality independently.

Further, we need to look into the legislative intent behind the Act as elaborated in the Ayyangar Committee Report of 1959. Here the intentions of the various statutes have been explained in detail. The report addresses the intent of mentioning an inventor for a particular patent as a matter of right of the inventor. The report emphasizes that any person has a moral right to be named as an inventor even though he might not have all the legal rights over the invention. The report said that the principle behind broaching the inventor for an invention was to facilitate the inventors to augment their economic worth for which they are justifiably entitled, even though they might have given away their proprietary rights by way of contracts or agreements. However, the AI can neither savor the benefits envisioned in the legislative intent nor can it be entitled to moral rights under prevailing laws in India.

Therefore, the overall study of the Act along with the above-mentioned case laws and the report on legislative intent, clearly clarifies that currently an AI cannot be recognized as an inventor in India. However, the AI related inventions are currently being recognized in India based on the fact that the AI is used as tool to assist the inventor.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Duty of disclosure – Information of foreign applications

Section 8 of the Indian Patents Act relates to furnishing information of foreign applications with the IPO. SECTION 8(1) of the Indian Patent Act mandates an Applicant to file an undertaking at the time of filing a Patent Application in India that the Applicant shall keep updating the Indian Patent office about the correspondence applications filed if any in foreign jurisdictions. Such updates have to be provided in Form 3 (Rule 12 (1)) till the date of grant of the Patent in India. Whereas, information under Sec 8 (2) has to be furnished when the Controller seeks detailed particulars corresponding to the foreign applications at any time during the prosecution of the Indian patent application.

“(1) Where an applicant for a patent under this Act is prosecuting either alone or jointly with any other person an application for a patent in any country outside India in respect of the same or substantially the same invention, or where to his knowledge such an application is being prosecuted by some person through whom he claims or by some person deriving title from him, he shall file along with his application or subsequently within the prescribed period as the Controller may allow—

(a) a statement setting out detailed particulars of such application; and

(b) an undertaking that, up to the date of grant of patent in India, he would keep the Controller informed in writing, from time to time, of detailed particulars as required under clause (a) in respect of every other application relating to the same or substantially the same invention, if any, filed in any country outside India subsequently to the filing of the statement referred to in the aforesaid clause, within the prescribed time.

2) At any time after an application for patent is filed in India and till the grant of a patent or refusal to grant of a patent made thereon, the Controller may also require the applicant to furnish details, as may be prescribed, relating to the processing of the application in a country outside India, and in that event the applicant shall furnish to the Controller information available to him within such period as may be prescribed.”

Timeline to file information under section 8

|

Section 8 (1), Rule 12 (2) |

If the other convention/NP applications were filed before the Indian convention/NP application was filed, the 6-month deadline is calculated from the Indian filing date.

|

If the other convention/NP applications were filed after the Indian convention/NP application was filed, the 6-month deadline is calculated from the date of filing of each corresponding foreign application. |

|

Section 8 (2); Rule 12 (3) |

Within 6 months from the date of communication from the controller seeking such details. |

|

Non-compliance of Sec 8 can be a ground for pre-grant, post-grant opposition and revocation under section 25(1)(h), 25(2)(h) and Sec 64(1)(m), respectively. There has been instances wherein the non-compliance of section 8 information has been used as one of the effective tools to revoke a patent.

|

Ajanta Pharma Limited v. Allergan Inc., Allergan India PVT. LTD

|

Allergan’s patent IN212695 was revoked |

|

Hindustan Unilever Limited's patent by Intellectual Property Appellate Board |

Hindustan Unilever Limited's patent IN 195937 was revoked. |

It shall be noted that the burden of proof lies on the Defendant (infringing the patent) to show that the primafacie case of section 8 has not been met by the Plaintiff. A mere statement without any facts and evidence to support that there has been violation of section 8 cannot be considered to institute a proceeding. In FRESENIUS KABI ONCOLOGY LIMITED V. GLAXO GROUP LIMITED & ANR, the FRESENIUS KABI ONCOLOGY LIMITED V. GLAXO GROUP LIMITED & ANR had failed to file furnish any facts and evidence to support their revocation petition.

Roche Vs Cipla decision: A landmark judgement was passed by the Delhi High Court in Roche Vs Cipla case on 2008 stating that a Patent cannot be revoked solely on the ground of non-compliance of section 8.

156. Consequently, the ground of violation of Section 8 read with Section 64(1)(m) is made out. However, still there lies a discretion to revoke or not to revoke which I have discussed later under the head of relief. Under these circumstances, even in case, the said compliance of Section 64(1)(m) of the Act has not been made by the plaintiffs, still there lies a discretion in the Court not to revoke the patent on the peculiar facts and circumstances of the present case. The said discretion exists by use of the word – may II under Section 64 of the Act. Thus, solely on one ground of non-compliance of Section 8 of the Act by the plaintiffs, the suit patent cannot be revoked”

WILFUL or UNINTENTIONAL SUPRESSION OF FACT

In KONINKLIJKE PHILIPS VS SUKESH BEHL CASE, the Delhi High Court stated that it is important to analyse if there has been suppression of information by the Plaintiff. Moreover, one has to consider if such suppression of fact was wilful or unintentional. Unintentional suppression of facts and information may be considered as one of the grounds to avoid revocation of patent under section 64 (1) (m). In this context, it is worth mentioning “Philips Electronics Vs. Maj (Retd). Sukesh Behl” case.

Philips Electronics sued Maj (Retd). Sukesh Behl, Proprietor of Pearl Engineering company for allegedly infringing Patent: No: 218255 entitled “METHOD OF CONVERTING INFORMATION WORDS TO A MODULATED SIGNAL” on 2012. The defendant filed a revocation petition under section 64 (1)(m) as the patentee or plaintiff failed to comply with Section 8 of the Act. The defendant contented that the plaintiff suppressed the vital information of the foreign applications corresponding to same or substantially same invention filed in India.

As a counter argument, Philips submitted an affidavit stating that additional information was inadvertently missed out by paralegal who failed to photocopy the back side of a document while submitting the application.

Decision of the Delhi High Court:

14. It requires to be noted that while the Plaintiff does not deny that a part of the information concerning the pending foreign applications was inadvertently not disclosed, there is no admission as to the withholding of that information being deliberate or that there was wilful suppression of such information. That surely would be a matter for evidence. Further, the question whether the non-disclosure of the above information contained on the reverse of the first page in the first instance before the COP was material to the grant of the patent raises a triable issue. It is not possible at the present stage for the Court to form a definitive opinion on the above aspects. If at the end of the trial the Court, after examining the evidence, agrees with the Defendants that the information that was withheld was material to the grant of the patent itself, it might proceed to revoke the patent. Alternatively, it might disagree with the Defendant and decline to revoke the patent. In other words, that determination would have to await the conclusion of the trial. For the aforementioned reasons, the Court is of the view that it is not possible to grant the prayer made in this application by the Defendant under Order XII Rule 6 CPC.”

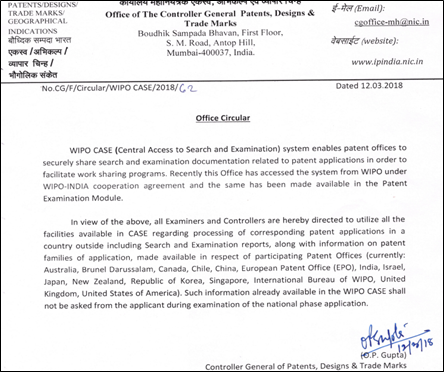

Moreover, recently the Indian patent office has issued a notification instructing the Examiners and Controller’s to utilise the WIPO case system and directed not to ask the Applicant’s about such details during prosecution of the national phase application.

CONCLUSION:

The purpose of inclusion of section 8 in the Indian patent Act is clearly mentioned in the Ayyangar report.

“It would be of advantage therefore if the applicant is required to state whether he has made any application for a patent for the same or substantially the same invention as in India in any foreign country or countries, the objections, if any, raised by the Patent offices of such countries on the ground of novelty or un patentability or otherwise and the amendments directed to be made or actually made to the specification or claims in the foreign country or countries.”

As mentioned in the Ayyangar report produced above, the sole purpose of submission of section 8 information to ease the prosecution of the patent application and help the Patent Examiner to prosecute the Patent application. Submission of Section 8 information is a procedural requirement to be complied by the Applicant till the grant of the patent. Non -compliance of such a procedural irregularity should not result in revocation of a patent that has overcome the hurdles of novelty and inventive step. It has been observed that the Delhi High Court has also stated the same in Roche Vs Cipla case. Further, prior to passing any harsh judgement against a patent, it is advisable to enquire if failure to comply with section 8 is done deliberately or unintentional. With the case law discussed in the preceding paragraphs it is worth mentioning that the jurisprudence with respect to section 8 is evolving. Procedural irregularity should not be considered as one of the tools to revoke a patent. Instead in case of non-compliance of such information, the Applicant should be given an opportunity to furnish such details, failure of complying to this opportunity may be considered to take a decision. Moreover, to avoid any such repercussions it is advisable that the Applicant and the representatives of the Applicant should diligently comply with Section 8, non-compliance of which would be used as an effective tool to invalidate a patent.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 84

- Next Page »

Follow

Follow